Seamless and scalable IT major incident management

As digital transformations continue to be implemented and business value chains become even more dependent on IT services, the impact on businesses and communities arising from unplanned outages continues to rise. In conjunction with this, organisations are experiencing a rise in cybersecurity attacks (Seals, 2017) placing further pressure on the availability of services and endangering the customer experience and loyalty.

IT organisations are seeking to understand how significant, wide-ranging business impacting incidents (especially cyber-security incidents) can be better managed and in particular what the role of the IT Major Incident Management (MIM), Security Operations and IT delivery teams should be during such incidents.

To further complicate this setting, enterprises may employ numerous incident management processes including Risk Management, MIM, Information Security Management, Crisis Management, and Business Continuity Management. Each of these processes employs varying roles to provide overall incident management, lead recovery operations and manage stakeholder communications. If not developed in an integrated fashion, these processes can present duplication of effort and induce confusion over roles and responsibilities in the end to end management of an incident as the incident escalates. This may lead to duplication in communications to stakeholders, duplication in management roles and responsibilities and duplication in post-incident reviews and continual service improvement.

To inform a seamless, scalable major incident management process, the Australasian InterService Incident Management System (AIIMS) provides industry-proven guidance that supports an integrated approach with the unity of command, functional management and management by objectives. AIIMS is an integral part of emergency management doctrine for the Australia fire and emergency services industry. The system provides a foundation for diverse teams (e.g. police, fire, ambulance, SES, volunteers) to resolve incidents effectively with the use of the same terminology, clarifying the roles, responsibilities and information flows.

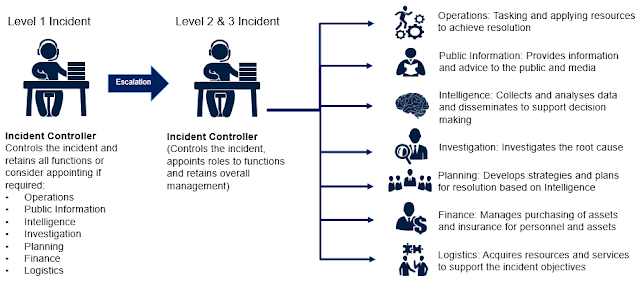

As seen below, AIIMS shows how major incidents are managed as a series of 7 integrated functions (e.g. Operations, Public Information, etc.) rather than a cohort of specialised technology teams (e.g App Dev, Middleware, etc). As the incident develops in size, impact or complexity, the Incident Controller may choose to delegate the responsibility of managing some or all of the incident management functions. While the Incident Controller may delegate responsibilities, they retain accountability for achieving the objectives of the incident. AIIMS employs a role-based MIM process with roles such as (and not limited to) Incident Controller, Deputy Incident Controller, Operations Controller, Public Information Controller, etc. This means that the Controller roles can be delegated to appropriate personnel as the incident escalates from IT major incident management to crisis management or business continuity management.

IT organisations are seeking to understand how significant, wide-ranging business impacting incidents (especially cyber-security incidents) can be better managed and in particular what the role of the IT Major Incident Management (MIM), Security Operations and IT delivery teams should be during such incidents.

To further complicate this setting, enterprises may employ numerous incident management processes including Risk Management, MIM, Information Security Management, Crisis Management, and Business Continuity Management. Each of these processes employs varying roles to provide overall incident management, lead recovery operations and manage stakeholder communications. If not developed in an integrated fashion, these processes can present duplication of effort and induce confusion over roles and responsibilities in the end to end management of an incident as the incident escalates. This may lead to duplication in communications to stakeholders, duplication in management roles and responsibilities and duplication in post-incident reviews and continual service improvement.

To inform a seamless, scalable major incident management process, the Australasian InterService Incident Management System (AIIMS) provides industry-proven guidance that supports an integrated approach with the unity of command, functional management and management by objectives. AIIMS is an integral part of emergency management doctrine for the Australia fire and emergency services industry. The system provides a foundation for diverse teams (e.g. police, fire, ambulance, SES, volunteers) to resolve incidents effectively with the use of the same terminology, clarifying the roles, responsibilities and information flows.

As seen below, AIIMS shows how major incidents are managed as a series of 7 integrated functions (e.g. Operations, Public Information, etc.) rather than a cohort of specialised technology teams (e.g App Dev, Middleware, etc). As the incident develops in size, impact or complexity, the Incident Controller may choose to delegate the responsibility of managing some or all of the incident management functions. While the Incident Controller may delegate responsibilities, they retain accountability for achieving the objectives of the incident. AIIMS employs a role-based MIM process with roles such as (and not limited to) Incident Controller, Deputy Incident Controller, Operations Controller, Public Information Controller, etc. This means that the Controller roles can be delegated to appropriate personnel as the incident escalates from IT major incident management to crisis management or business continuity management.

An AIIMS instrument that will improve the management of and focus within the MIM team during an incident is the Common Operating Picture (COP). This instrument can be an MS Word document or specific form/tab in an IT Service Management tool (or ticketing system) that is shared to all incident team members via a desktop screen application or a ChatOps session by the Incident Controller. The COP induces focus on the key elements of managing a major incident such as the current objectives, the situational status, who is engaged and what resolution activities have already been attempted. The COP helps onboard new responders to the incident by providing them with key information without distracting the Incident Controller. The COP informs communications to key stakeholders and can be easily leveraged for post-incident reviews.

A similar example to AIIMS being used by an IT organisation is Google’s incident management system which is based on the US Federal Emergency Management Agency’s National Incident Command System (NICS) which is known for its clarity and scalability (Beyer, Jones, Petoff & Murphy, 2016). In their book Site Reliability Engineering, Beyer et al. identified the following key attributes of a successful incident management system:

1 Recursive Separation of Responsibilities: the need for several distinct roles should be delegated to particular individuals and these roles include Incident Command, Operational work, Communication and Planning. These NICS roles are similar to those suggested in AIIMS and allow for the delegation of roles as the incident increases or decreases in impact.

2 A Recognised Command Post: employing a physical or virtual ‘War Room’ to help coordinate management, resources and communications for an incident. Google leverages bots in IRC room to log incident-related traffic for post-mortem analysis.

3 Live Incident State Document (LISD): similar to the Common Operating Picture, the LISD is maintained by the Incident Controller as an active representation of the incident. Google uses their Google Docs or Sites to host this LISD with their geographically dispersed teams.

4 Clear, Live Handoff: At the end of each shift, the outgoing Incident Controller is required to provide a handoff (or handover) to the incoming Incident Controller to ensure an effective knowledge transfer and therefore reduce the delay in restoring services from repeating analysis and investigation.

To summarise, IT organisations can avoid the challenges of employing varying incident management processes (and therefore reduce service recovery time) by leveraging a scalable MIM process that utilises a series of integrated and delegated functions rather than a cohort of specialised technology teams. This approach enables a severe incident to be efficiently transferred between MIM, crisis management and business continuity management by focusing on functions that can scale rather than escalating between processes. While AIIMS and NICS were both developed for emergency services, their concepts are beneficial in the context of IT operations as highlighted in Google’s Site Reliability Engineering.

References:

Beyer, B., Jones, C., Petoff, J. & Murphy, N. (2016) Site Reliability Engineering. O’Reilly Media, Inc. IBSN 978-1-491-92912-4

Seals, T. (2017). Cyber-attack Volume Doubled in First Half of 2017. Retrieved May 21, 2018 from https://www.infosecurity-magazine.com/news/cyberattack-volume-doubled-2017/

Comments

Post a Comment